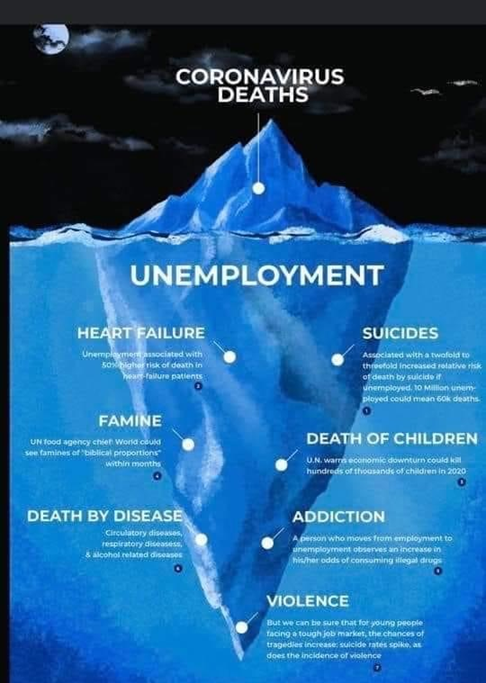

All over the news we see headlines about the projections of those who will suffer unemployment related to the economic shutdown caused by the COVID-19 response. As of May 4, 2020, 30 million people filed claims for unemployment, suggesting that the unemployment rate could reach a projected 32 percent next quarter —well above the rate at the height of the Great Recession (25%).

Black Americans historically have an unemployment rate that is twice as high as the overall rate, even in a healthy economy. Unemployment means different things to different people. For some it means the rent won’t get paid (then some landlords won’t be able to pay mortgages), others will fall behind on their property taxes (the majority in most towns go towards school expenses), some parents will not be able to pay college tuition, others, who are fortunate enough to have savings, might have to cash those out in order to survive economically until this ends. With no end date in the horizon, it is easy to catastrophize how far the trickle down of the economic shutdown will lead us. Clearly, this action is necessary to protect human health; when people’s lives are at stake, money doesn’t matter as much, does it? Unfortunately, employment and financial standing, are directly and intricately intertwined so closely with health, that we can’t ignore the health consequences that creating a mass of newly unemployed people will cause.

Black Americans historically have an unemployment rate that is twice as high as the overall rate, even in a healthy economy. Unemployment means different things to different people. For some it means the rent won’t get paid (then some landlords won’t be able to pay mortgages), others will fall behind on their property taxes (the majority in most towns go towards school expenses), some parents will not be able to pay college tuition, others, who are fortunate enough to have savings, might have to cash those out in order to survive economically until this ends. With no end date in the horizon, it is easy to catastrophize how far the trickle down of the economic shutdown will lead us. Clearly, this action is necessary to protect human health; when people’s lives are at stake, money doesn’t matter as much, does it? Unfortunately, employment and financial standing, are directly and intricately intertwined so closely with health, that we can’t ignore the health consequences that creating a mass of newly unemployed people will cause.

The United States is one of the few countries where people’s access to healthcare is directly tied to their employment status. About half of all Americans get their health insurance through their employer. Though some people can purchase COBRA benefits from their employer for 18 months following employment separation, many end up unemployed and without medical or prescription drug insurance. The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) is a health insurance program that allows eligible employees and their dependents the continued benefits of health insurance coverage when an employee loses their job or experiences a reduction of work hours.

Those without the ability to afford COBRA, can apply for Medicaid or family care benefits, but those who do not qualify end up with no insurance. Earlier this month, the Economic Policy Institute reported that 3.5 million workers are at high risk of losing their employer-provided health insurance. This means that many families will forgo preventative care, postpone dental cleanings and check-ups, and cancel elective and other scheduled surgeries. Numerous researchers have found a direct connection between being uninsured and death. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) estimated that 18,314 Americans aged between 25 and 64 years die annually because of lack of health insurance. One study conducted by the Harvard Business School and the Cambridge Alliance, estimated that lack of health insurance causes 44,789 excess deaths annually.

Those without the ability to afford COBRA, can apply for Medicaid or family care benefits, but those who do not qualify end up with no insurance. Earlier this month, the Economic Policy Institute reported that 3.5 million workers are at high risk of losing their employer-provided health insurance. This means that many families will forgo preventative care, postpone dental cleanings and check-ups, and cancel elective and other scheduled surgeries. Numerous researchers have found a direct connection between being uninsured and death. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) estimated that 18,314 Americans aged between 25 and 64 years die annually because of lack of health insurance. One study conducted by the Harvard Business School and the Cambridge Alliance, estimated that lack of health insurance causes 44,789 excess deaths annually.

Mental Health Compromises

The rise in unemployment is increasing the mental health crisis in the United States and at the same time many Americans face barriers to receiving mental healthcare. People who are unemployed tend to have more mental health issues including depression, anxiety, stress, as well as higher levels of psychiatric hospital admissions. What are the non-monetary benefits of work? Sense of purpose and meaning, social support, intellectual stimulation, sense of identity. When one is unemployed, not only is their usual source of income gone but also their personal work relationships, daily structure and sense of purpose.

The rise in unemployment is increasing the mental health crisis in the United States and at the same time many Americans face barriers to receiving mental healthcare. People who are unemployed tend to have more mental health issues including depression, anxiety, stress, as well as higher levels of psychiatric hospital admissions. What are the non-monetary benefits of work? Sense of purpose and meaning, social support, intellectual stimulation, sense of identity. When one is unemployed, not only is their usual source of income gone but also their personal work relationships, daily structure and sense of purpose.

Physical Health Compromises

Physical Health Compromises

Studies have shown that unemployment and fall in income may lead to obesogenic diets or be associated with health risk behaviors such as excessive alcohol consumption, drug abuse, increased smoking and decreased physical activities. Chronic disease (cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and musculoskeletal disorders), and premature mortality emerge and have also been linked to unemployment. Many develop a stress-related condition, such as stroke, heart attack, heart disease, or arthritis.

Employees who are unable to work in the United Kingdom have been receiving 80% of their salaries from the government. This measure has stopped employees being laid off due to the coronavirus pandemic. It has enabled the employers to keep their jobs, even if their employer could not afford to pay them. Canadian and European governments like Germany are also paying part of their workers’ salaries to ensure they don’t lose their jobs. This is not the case in the United States where millions of people have lost their jobs over the past weeks. Many Americans have reported feeling insecure, stressed and worried about their financial situation. Most low wage workers who experienced layoffs in large cities reported feeling fretful, angry, irritable and depressed. Once people are unemployed, they tend to earn less once they find new jobs and they have children with worse academic performance than similar workers who avoided unemployment.

Understanding the underlying mechanisms through which time out of work relates to outcomes both during and after unemployment is essential in devising effective policies to ameliorate the consequences of job loss. The duration of unemployment and economic hardship have numerous negative effects; thus, policy actions must place greater emphasis on providing additional support.

Join the Conversation