The #1 Netflix documentary the week of March 29, 2020 was the Tiger King; Murder, Mayhem and Madness, a bizarre docuseries about big cats and the people who collect them. The rise of popularity of the series was attributed to the fact that most Americans were under stay at home orders related to the COVID-19 pandemic. At first glance, it appears that this is where the connection ends, but when we dive deeper in our understanding of the Corona pandemic’s origins, the events seem ironically related.

The #1 Netflix documentary the week of March 29, 2020 was the Tiger King; Murder, Mayhem and Madness, a bizarre docuseries about big cats and the people who collect them. The rise of popularity of the series was attributed to the fact that most Americans were under stay at home orders related to the COVID-19 pandemic. At first glance, it appears that this is where the connection ends, but when we dive deeper in our understanding of the Corona pandemic’s origins, the events seem ironically related.

The Tiger King, for the few who haven’t watched it, was a documentary about people in the US who “own” large, wild cats such as tigers, lions, and leopards. Some possess these animals and engage in commerce in the form of roadside zoos (Joe Exotic), others assume loftier status as operating “sanctuaries” (“That Bitch, Carole Baskin”). The issue underlying the drama that unfolds, is the legality of keeping wild animals under the Endangered Species Act. Both Joe Exotic and Carol Baskin were keeping wild animals on their property for the purpose of commerce, with no regards to the animal’s natural habitat, believed they were acting in the animal’s best interest, but they both could clearly see the other was not.

Ultimately, Joe Exotic was convicted on federal charges of animal abuse and violation of the Endangered Species Act (and attempting to hire someone to murder Carole Baskin) for this mistreatment of the animals. Current law prohibits poaching of wild animals and breeding wild animals in captivity. Additionally, the Endangered Species Act was passed for the purpose of preventing the extinction of animal species and the acknowledgment that extinction of any species can have a dramatic impact on the overall ecosystem. The Endangered Species Act protects animals from wildlife exploitation, such as illegally keeping wild tigers as pets or selling smuggled animals in a live animal market…

Ultimately, Joe Exotic was convicted on federal charges of animal abuse and violation of the Endangered Species Act (and attempting to hire someone to murder Carole Baskin) for this mistreatment of the animals. Current law prohibits poaching of wild animals and breeding wild animals in captivity. Additionally, the Endangered Species Act was passed for the purpose of preventing the extinction of animal species and the acknowledgment that extinction of any species can have a dramatic impact on the overall ecosystem. The Endangered Species Act protects animals from wildlife exploitation, such as illegally keeping wild tigers as pets or selling smuggled animals in a live animal market…

Enter COVID-19

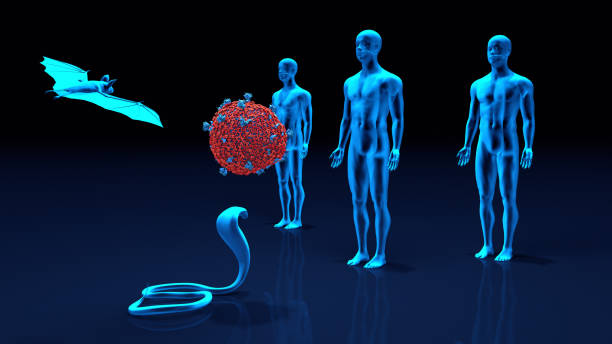

COVID-19 is a zoonotic disease. This occurs when an endemic virus in an animal jumps to humans and can sustain human to human transmission. Genomic analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 shows that the ancestral strain of the virus originated in bats. How it got from bats to humans is less clear, and likely involved a different animal as an intermediary. Although accidental release from research laboratories cannot yet be ruled out, circulating coronavirus strains in pangolins are most closely related to the pandemic virus, making pangolins the most likely animal intermediary. When a zoonotic transmission first occurs, the virus is more virulent but spreads less inefficiently. With no population immunity, the virus has time to adapt and spread more efficiently which results in decreasing virulence. This evolutionary process takes time, and as a result, zoonotic infections can be very deadly when the virus first jumps from animal to human.

COVID-19 is a zoonotic disease. This occurs when an endemic virus in an animal jumps to humans and can sustain human to human transmission. Genomic analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 shows that the ancestral strain of the virus originated in bats. How it got from bats to humans is less clear, and likely involved a different animal as an intermediary. Although accidental release from research laboratories cannot yet be ruled out, circulating coronavirus strains in pangolins are most closely related to the pandemic virus, making pangolins the most likely animal intermediary. When a zoonotic transmission first occurs, the virus is more virulent but spreads less inefficiently. With no population immunity, the virus has time to adapt and spread more efficiently which results in decreasing virulence. This evolutionary process takes time, and as a result, zoonotic infections can be very deadly when the virus first jumps from animal to human.

75-80% of new and infectious diseases are zoonotic. Deadly pandemics are made possible by human behaviors such as selling smuggled pangolins in an open, live animal market in China, or by illegally keeping wild tigers as pets in America. The way we house farm animals for food production, crowding tens of thousands in small, unsanitary conditions serve as “amplifiers” for viral pandemics. In 2009, the H1N1 swine flu outbreak originated in a pig confinement operation in North Carolina. In 1997, the H5N1 bird flu outbreak originated in Chinese chicken farms. Though this method of transmission is not the only way pandemics occur, meat production methods are one thing over which humans can easily control. There are methods of meat production that are sustainable, less likely to breed disease, and more humane for the livestock.

75-80% of new and infectious diseases are zoonotic. Deadly pandemics are made possible by human behaviors such as selling smuggled pangolins in an open, live animal market in China, or by illegally keeping wild tigers as pets in America. The way we house farm animals for food production, crowding tens of thousands in small, unsanitary conditions serve as “amplifiers” for viral pandemics. In 2009, the H1N1 swine flu outbreak originated in a pig confinement operation in North Carolina. In 1997, the H5N1 bird flu outbreak originated in Chinese chicken farms. Though this method of transmission is not the only way pandemics occur, meat production methods are one thing over which humans can easily control. There are methods of meat production that are sustainable, less likely to breed disease, and more humane for the livestock.

Wildlife Poaching

The global trade in wildlife leads to disease transmission that cause both human disease outbreaks and threatens livestock and native wildlife populations, thereby negatively impacting the health of local and global ecosystems. Because the global trade is conducted illegally or through informal networks the magnitude of the issue is hard to quantify. Some estimates indicate upwards of millions of animals are globally traded each year:

The global trade in wildlife leads to disease transmission that cause both human disease outbreaks and threatens livestock and native wildlife populations, thereby negatively impacting the health of local and global ecosystems. Because the global trade is conducted illegally or through informal networks the magnitude of the issue is hard to quantify. Some estimates indicate upwards of millions of animals are globally traded each year:

- 40,000 live primates

- 4 million live birds

- 640,000 live reptiles

- 350 million live tropical fish

According to the Asian Animal Foundation, live wildlife in markets in China sell, barter, and trade in many species of animals; masked palm civets, ferret badgers, barking deer, wild boars, hedgehogs, foxes, squirrels, bamboo rats, gerbils, various species of snakes, and endangered leopards, domestic dogs, cats, and rabbits. Humans need to reconsider the impact of taking wildlife out of their natural habitats, habitats their immune system have evolved to thrive in, and understand that possessing those animals has consequences to animal, human, and environmental health. Global pressure needs to be put on the international community to stop the practice of poaching wildlife, selling wildlife, at wet markets, and (sorry, Joe Exotic) keeping wild animals in captivity. (April 5, 2020 a Tiger at the Bronx Zoo was the first tiger to test positive for COVID-19).

Bringing it Back to Tiger King

The heart of the controversy in the Tiger King was the belief in the underlying motives of those who collected the big cats; were they harming the animals or helping them? Though these wild tigers and leopards, living in captivity, were given food, water, shelter, and affection by their “owners” many believe in that it was inherently abusive to keep the wild animals living in captivity. Philosophical beliefs about humane treatment of animals notwithstanding, the mere act of proximity to wild species of animals, not intended for direct human interaction, put humans at risk for novel virus exposure. When our choice to smuggle wildlife as pets or our development of the land encroaches on the habitats and ecosystems of wild species, leave us interacting more regularly with animals that were not intended to have regular human contact, viral pandemics are likely to occur more frequently.

The heart of the controversy in the Tiger King was the belief in the underlying motives of those who collected the big cats; were they harming the animals or helping them? Though these wild tigers and leopards, living in captivity, were given food, water, shelter, and affection by their “owners” many believe in that it was inherently abusive to keep the wild animals living in captivity. Philosophical beliefs about humane treatment of animals notwithstanding, the mere act of proximity to wild species of animals, not intended for direct human interaction, put humans at risk for novel virus exposure. When our choice to smuggle wildlife as pets or our development of the land encroaches on the habitats and ecosystems of wild species, leave us interacting more regularly with animals that were not intended to have regular human contact, viral pandemics are likely to occur more frequently.

As we explore ways to response to COVID-19, and future pandemics, prevention strategies should be explored; the way we treat animals have health implications to human populations. Our collective future might depend on us forging a path where all species can live harmoniously, and perhaps separately, in order to decrease virus spillover.

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2009-02/asu-so1020909.php

She also studied viruses like H5N1 bird flu in 2009.