USA TODAY

November 12, 2019

At such a young age, she could not understand how much it meant to him, a man on parole, to have his voice included in the chorus of American voices guiding our democracy.

Citizens across the nation voted on a number of initiatives, some local, some statewide, that affect their lives and their communities. Their participation in the democratic process is an important and vital aspect of building strong healthy communities. While parolees can vote in New York due to an executive order by Gov. Andrew Cuomo, approximately 50,000 people incarcerated in New York cannot. There are less than a handful of states in which incarcerated people can.

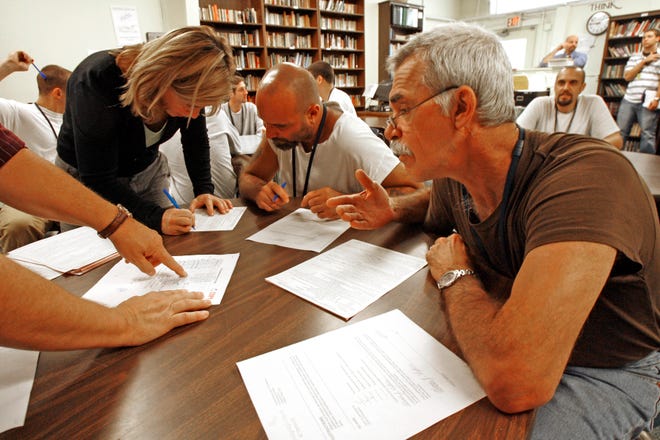

Missy Shea of the Vermont Secretary of State’s office, left, helps inmates at the Marble Valley Regional Correctional Facility through the voter registration process in Rutland, Vt., on Oct. 2, 2008. Many of the inmates took the equivalent of a civics course at the prison’s high school where they learned that even though they were incarcerated, they could vote. Toby Talbot/AP

During this period of unprecedented momentum in prison reform, we’re also realizing how misguided and wrong America’s approach to the carceral system is. It turns out that prisons, with their rampant abuse of authority and cruel extrajudicial punishments, are far from a solution to public safety and actually make our streets more dangerous by failing to provide the support networks and mental health resources needed for success.

The effect is to further isolate people in prisons from the outside world. We now know that incarcerated people who are regularly visited by family members and friends maintain healthier ties to their communities, are better adjusted when they reenter society and are less likely to recidivate.

When we deny people in prison the right to vote, we sever yet another vital connection to society: civic engagement.

In Maine and Vermont, incarcerated citizens maintain their right to vote. They register their peers in prison. They have a sense of belonging and contributing to the vitality of their communities that sets the stage for a successful reentry process.

As a society we will benefit in multiple ways by eliminating felony disenfranchisement. Groundbreaking research by Professor Hedwig Lee reveals that families with incarcerated loved ones are less likely to engage in the voting and elections process. If a family member’s earliest experiences in the public realm place them in a fractured, adversarial relationship with our institutions, they develop an identity in which they live outside our systems.

In the United States there are about 2.3 million people currently incarcerated. In addition to these 2.3 million disenfranchised individuals, there are many more civically disengaged family members. When thinking about the disproportionate impact of incarceration on poor black and brown communities, this lost voting power is a significant matter of concern.

Many of us have been conditioned to just assume that incarcerated people can not and should not vote. For the past year, members of Alliance of Families for Justice have been meeting with members of the New York State Assembly and Senate to share our concerns that this assumption has far too many collateral consequences for our communities and our democracy. Issues of low voter turnout and apathy can be reversed, and new life can be infused into marginalized communities.

Recently, New York State legislators have revealed their concrete interest in reversing felony disenfranchisement by drafting bills that would enable New York to follow the progressive and sound leadership of Maine and Vermont and allow individuals to vote while incarcerated. That sets a strong example for the rest of the country.

For that 9-year-old, her dad, and others like them, opening up voting roles is what a true democracy means.

Jill “Soffiyah” Elijah

Executive director, Alliance of Families for Justice

Brooklyn, N.Y.

Join the Conversation